Extreme Extinction Event!

Part 2 – Rapid Burial

Welcome back to our next session of Literal Genesis, which is actually lesson 10, but it's part two of the Extreme Extinction Event, where we've been talking about evidences for the global flood. And if you haven't heard me say this before, I'm going to say it again, hopefully you've remembered this by now, that our aim in Literal Genesis is to hold firmly to scripture and hold loosely to theories, because scripture never changes. In fact, Genesis 1:1, "In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth" has read the same way for thousands of years. Yet the theories of us flawed human beings, or scientific theories, they change all the time. They're under constant flux.

Now, what I want to be very clear, I don't want this to be the idea that this is God versus science or scripture versus science, because if you think about that, that's actually a contradiction of terms. Because God, if you want to think of it this way, was the first scientist. Although God doesn't need to study to learn, He already knows all facts, but He did create the laws of physics, which govern our universe. He created the matter, He created energy. So it makes no sense to say that this is in any way, God versus science. Rather, what this is more about is how do we as apprentice scientists or junior scientists, if you will, how do we interpret the living things, the world that we look at and examine through the lens of the ultimate scientist or the ultimate creator, and that is God. We want to be sure we get our interpretations right.

Now, in our last session, we discussed the trillions and trillions of fossils that we find all over the rock layers around the globe. And we looked at this as an evidence to support the idea that the entire earth was flooded with water, and lots of things died in that flood. And today, we'll look at a second evidence of this mass extinction event, which is rapid burial.

Rapid Burial

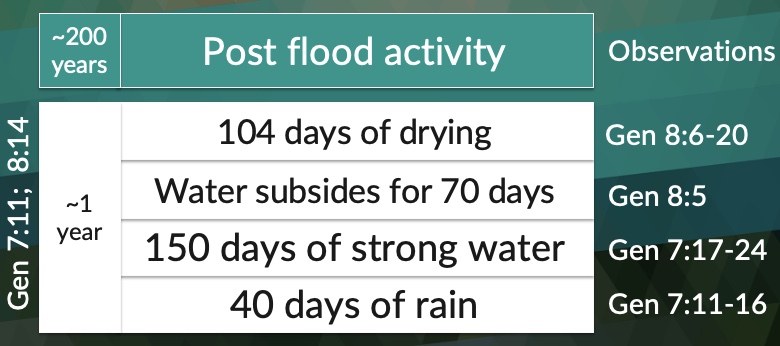

You see, the slow and gradual process that we're normally taught, that these rock layers took millions and hundreds of millions of years to grow over time and bury things slowly, that's one idea, right? That's a theory. But what do we do with theories? We hold loosely to theories, right? The other idea is that if we look at it through the lens of scripture, it would have been a rapid burial event because the flood lasted a year. In fact, we'd really have less than a year because there was about 104 days of drying. So we have less than a year to bury all these things and create the rock layers.

Now, when we go out and do our science, we need to figure out which one makes the most sense. As always, we start with scripture,

All flesh that moved on the earth perished, birds and cattle and beasts and every swarming thing that swarms upon the earth, and all mankind;

- Genesis 7:21

So here in Genesis 7:21, we find out where the living things came from, that we find buried in the rock layers. Well, they were the living things that were alive during the time of the flood. And Genesis six, seven, and eight tells us of the events that would have buried all of these living organisms during the small timeframe, during less than a year timeframe.

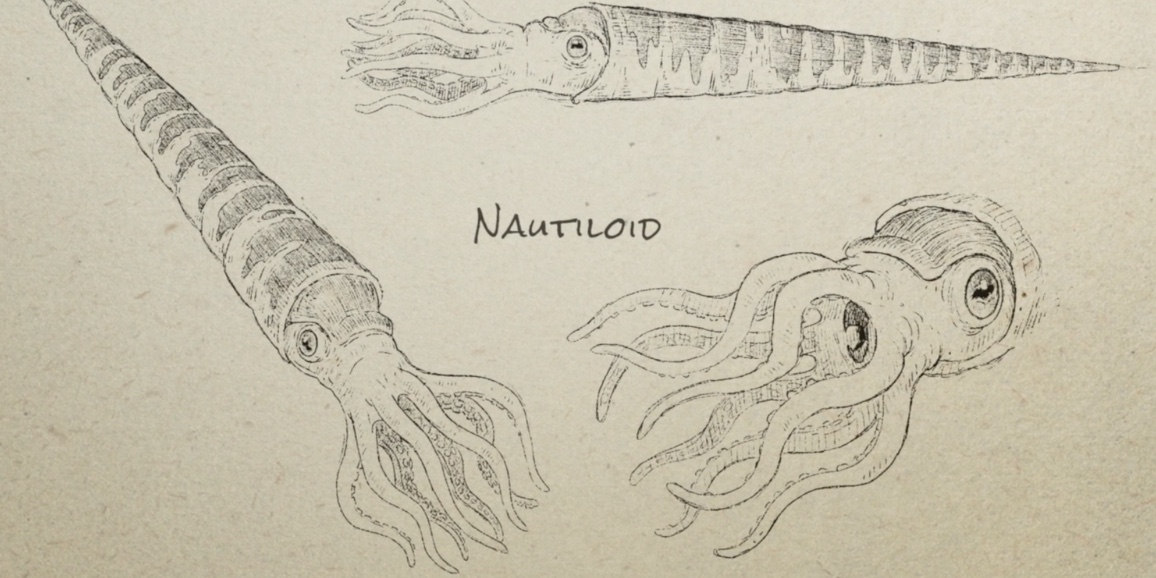

And so, what we're going to look at today is, is there any other evidence to support the idea that this happened very rapidly? And the first thing we want to look at is something called a nautiloid. Now I kind of stole these drawings from Dr. Steve Austin. He's a geologist. I believe he received his PhD in sedimentary geology from the University of Pennsylvania. So these are his drawings. You'll see a couple more of these in the first few slides, but the nautiloid in particular is an extinct cephalopod, and the word cephalopod literally means head foot.

Redwall Limestone- Nautiloids

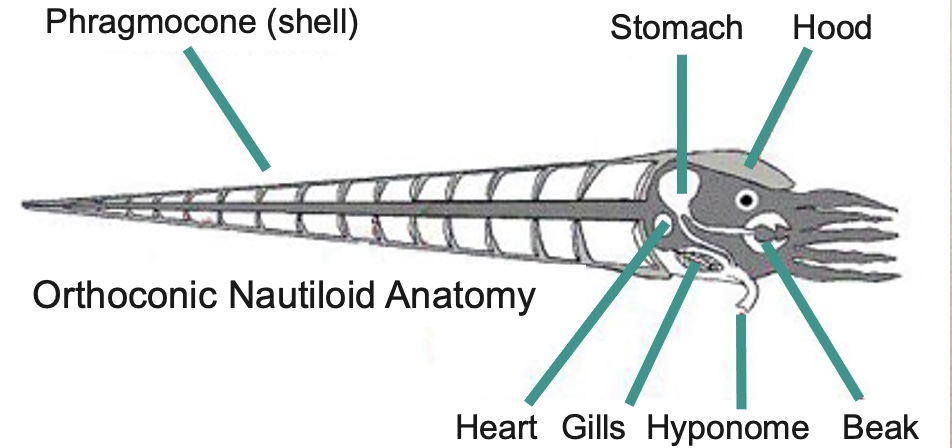

And if you look at the cephalopod, there's the head and there's the foot. So it matches, right? On the left we have a cephalopod. And this particular nautiloid has a straight shell. The nautiloid that we see today in the oceans are very rare. Nowadays we find there's more of a curved, spiraled shell. We find lots of those in the fossil record as well. Now, these nautiloids would grow to lengths of more than two feet. We find them in the fossil record, sometimes 12, 15, 19-feet long. Can you imagine getting in the water and seeing this guy here, 19-feet long swimming around you? That would be very unsettling to me. And in fact, he has a near cousin that gets even longer than that, 35, 75 feet. There were some very, very huge things in the past that we just don't have today.

The nautilus would have an eye, as you see here, obviously, that was very well adept for seeing in the dark, we know from living counterparts. In fact, the nautilus that we see today is often called a living fossil, because there's very little change between the nautilus we see today and the ones we find in the fossil records that are supposedly 500 million years old. Again, where's that change, right? Where's that evolutionary change?

The nautilus can go down very deep, a couple of thousand feet deep, in the ocean. And it was once thought that the nautilus would kind of hang out there during the day, then migrate up at night to feed, but now we see that it's a little more complicated than that. They still migrate vertically, up and down, but they hang out at different depths for different times and it's really interesting.

The other thing that we want to point out on the nautilus here is the anatomy. And I'm not going to go over all these terms here, just a couple, starting with the shell. So we see it's the very front part of the shell, this is called the living chamber. This is where the animal actually lived, like the living room, if you will. And then the rest of these chambers are empty or full, depending on if the animal needs to go up or down. So if you think about a submarine and how they may fill certain compartments with water to dive and then empty that water out to rise, it's similar, only that the nautilus does it in a very, very different way. There are pumps involved, but not the way you think.

First of all, we'll look at this thing here, running down the center of the nautiloid, that's called the siphuncle- kind of fun to say. The siphuncle is a tube that runs through these chambers, and through the process of osmosis can adjust the ratio of gas to liquid in these chambers. It's absolutely fascinating. Now, in evolutionary terms, think about this, we're going back 500 million years to the beginning of life at the Cambrian area. Now, again, I don't believe in these long ages, but we'll refer to them this way for our purposes today. Right off the bat, you've got a very complex organism that's using osmosis to change the ratio of liquid to gas. In fact, when this animal needed to raise, to go into shallow waters, what it would do is use ion pumps in the siphuncle to adjust the ions. It would pull the ions from these chambers into the siphuncle, and the liquid would want to follow the ions into the siphuncle, and then it could be moved up to the mantle, or it could be released.

At the same time when the liquid was empty, the gases in the blood, primarily nitrogen, but also oxygen and carbon dioxide, would fill these chambers and then they would cause the animal to rise. To reverse things, when it wanted to dive, it would put ions into the chambers, water would follow or this liquid would follow, and it would cause it to dive. Not a simple process at all. And by the way, guess what these ion pumps work off of? ATP.

Remember our discussion of ATP in the cell, how there's no free lunches, right? If you're going to have energy, you need something to burn fuel. And so already we have these complex ATP engines at work in this early life form, if we're talking about the evolutionary timescale.

And the other thing I want to point out here is this thing called a hyponome, this little hook-like tube feature here. So this would actually give the nautiloid a jet propulsion-type capability. So if you think about the animal drawing water in through the mantle, which is up here in the cavity, and then pushing its body against the back wall, after it seals off the mantle, the water has one way to go out and that's out this little tube here, the siphuncle. And if it's pointing backwards, the animal would go forward, if it's pointing forward, the animal could go backwards very rapidly, much faster than it could go forward.

And I did bring an illustration. This is a fossilized nautiloid (see video 9:23). I believe this one here comes from Morocco. There are lots and lots of ones we see in Morocco, because in Morocco there happens to be this Cambrian layer of rock, which is very near to the ground. It's not deep, it's very close to the surface. And you find all kinds of Cambrian-era creatures in there.

Now, just a little bit of a sneak preview, in the next session, we'll talk a little bit more about some of these layers and what they might mean, but here we see two of these, these nautiloids: one is not cut open, the other is kind of sliced open on the top. And you can see here this line running through the center of this nautiloid, that's the siphuncle. This is that hollowed tube where we'd have that exchange of ions and where we could regulate the buoyancy of the animal. Then if you see these, these vertical lines going down here, they're bigger at this end, smaller at this end. These are the chambers, right, where we had the liquid and the gas exchange, and then these lines or these walls are actually called septa or septum for singular. And so you can see in this cross-section here, it's very nicely done, and it's all polished. So it looks all shiny. But this nautilus, again, is very complicated right off the bat in the Cambrian layer of rocks.

Okay, so what about this nautilus, can we talk about here? Here's a picture of a very, very blurry finger. I'm just kidding. It's a finger pointing to a nautilus in the rock. So this is from the Redwall Limestone in the Grand Canyon.

I believe this may be another one of Dr. Austin's pictures, but you can kind of see the outline of the nautilus here, there's the pointy end, and then just in here it gets bigger where the creature would have lived. So, you know, if you're out looking for fossils, these are the kinds of patterns you want to look for, patterns that exist in nature, but aren't necessarily found in the rocks. And when you spot something like that, you take a closer examination.

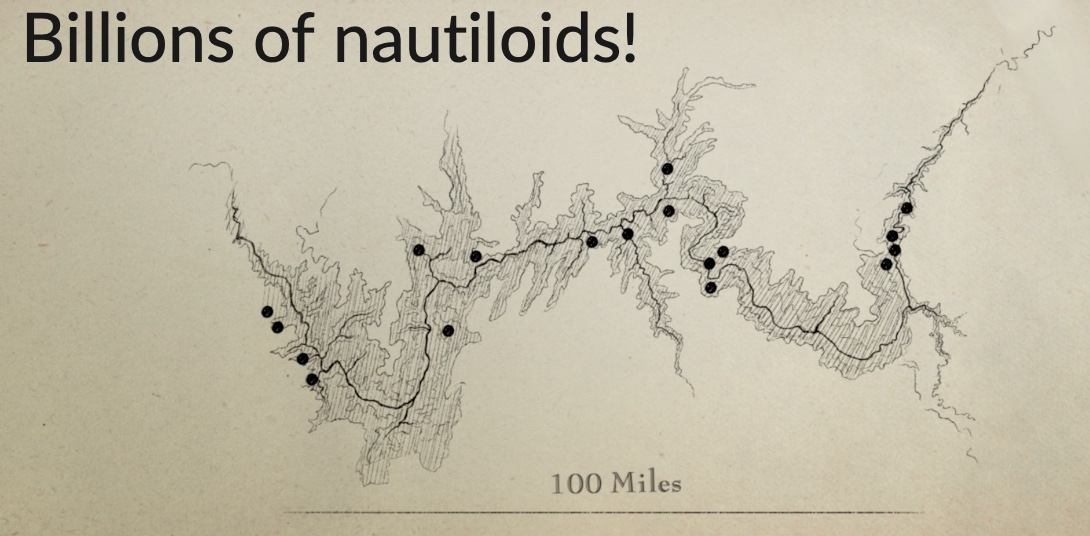

So what's so significant about these nautiloids in the Grand Canyon? Now, I've been fortunate enough to go to the Grand Canyon on a rafting expedition and examine these layers. And I've seen the Redwall Limestone myself. Dr. Austin, though, he's been doing this for 25 years, studying these nautiloids in the Grand Canyon. And if you see these dots in the image below represent finds or these fossil nautiloids. Over a 100-mile section of this Redwall Limestone.

And this Redwall Limestone goes on in a large sheet for many miles, through Las Vegas, upwards north, down south, southwest. So it's a big, big piece of rock, this Redwall Limestone. But he's estimating that just in this 100-mile section here alone, there are billions of these nautiloids.

This section that we're talking about here, the Redwall Limestone is about 500-800 feet thick. In some places it's over a thousand feet thick. So it's a pretty good piece of rock itself. And in the upper seven feet of this Redwall Limestone is where we find these nautiloid fossils, just in the upper seven feet.

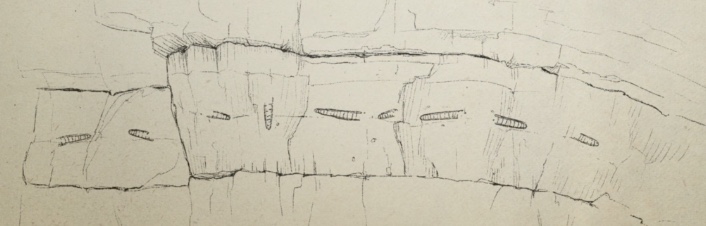

And what Dr. Austin has discovered, and has written extensively about over 25 years, is that all of these fossils in the seven-foot layer are horizontal, they're either pointing one way or pointing the other but they're horizontal, and about every seventh one is vertical. About one out of every seven is vertical, the rest are horizontal.

Now, we have two competing ideas as to what happened here. One is in the lens of the scripture where we had a flood, which we'll talk more about in a moment. The other is that this limestone accumulated at an incredibly slow rate, about one foot every thousand years. So for seven feet to accumulate, that would be about 7,000 years, right? If I'm doing the math right, I think that's an easy one, 7,000 years.

So in the past, when these nautiloids died, they would obviously sink to the bottom because of their shells, they were denser than the water, so they would sink down. And if you think about it, would you expect to find these nautiloids in these mostly horizontal positions, facing the same way? Wouldn't one be facing this way, one be facing this way, one be facing that way? It would encompass the full circle, right? But they're not, they're all facing relatively the same direction.

And then, every seventh one is vertical, that's very puzzling. How do you get a nautiloid to die, sink to the bottom and stay vertical while it's buried over thousands of years? That doesn't make a lot of sense. That's one idea, right? That's the competing idea, that's the traditional geological idea, the slow and gradual burial. However, it makes more sense, as Dr. Austin states, to look at these as being washed in place by a current. That's why they're relatively all in the same spot.

Now, these vertical ones here, if you think about that nautiloid changing depths: going up, going down, and some of these are pointing out, some of them are pointing down. But the vertical ones, what could have happened to have caused them to be frozen in time in this vertical position? Again, some massive layer of sediment came washing in, and these nautiluses were just frozen where they were, right? They were washed in to place with the current and then froze in their position. That makes a lot more sense to me, rather than this idea that they were slowly and gradually buried over great periods of time.

So again, we're looking at evidences for rapid burial, and we see one right here. This is not the only place. In every sedimentary layer around all places, around the globe, we see similar things. We see, in fact, that the sediments themselves give testimony that they were washed in place.

So if these organisms died a natural death, they fell to the bottom of a calm sea- because that's the story, right? That North America was underwater, in shallow placid seas, it was a calm time, right? Nothing exciting or catastrophic going on. Then they would be randomly pointing and they're just simply not randomly pointing. And what does this imply? Again, it implies that they were washed in via a water event and they were frozen in place.

Sedimentary Layers

So let's look at the sedimentary layers themselves just for a moment. Now, this is my drawing. I never said I was any kind of an artist, but hopefully this will get the point across.

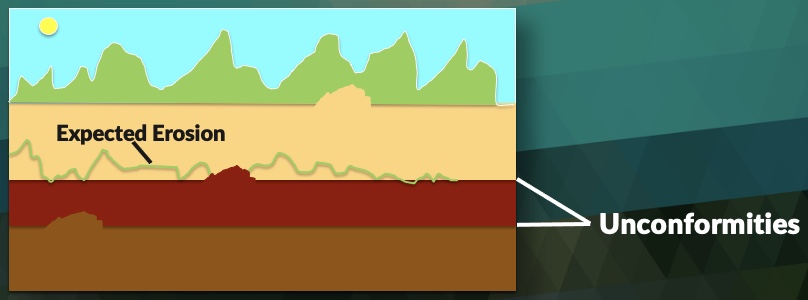

And what we're looking at here, on the upper layer, the blue is the sky and there's the sun right there, a little yellow circle. Then we had the landscape here, that we're kind of walking on today. And then underneath this, we had these sedimentary layers. And the idea is that from top to bottom, that this took millions, hundreds of millions of years to accumulate. In fact, let's just go all the way back to the Cambrian era, when we had the first sedimentary layers with the first set of fossils, right? The Cambrian area.

And so, we'll call this Cambrian down here. Now I've got three layers, obviously there's a whole lot more than three layers. And this is very, very thick on the planet. But this took, let's say, 550 million years to accumulate all this. So this layer took hundreds of millions of years, this layer hundreds of millions, hundreds of millions, and then here we are today.

Now, right off the bat, I think you'll notice something a little different about these layers. We have flat, relatively flat layers, and we can see this so easily in the Grand Canyon. In fact, it's probably the best spot in the world, to examine these layers and see how flat that they are. So we have flat, flat, flat, and then they get this flat layer on top, that is actually not so flat, is it? Well, why isn't this flat on top? Everything else is flat below it.

Well, obviously we have erosional characteristics on the surface of the earth. Lots of erosion going on. We have hills, we have valleys, we have mountains, and this is what we're used to. So the question here is, over this 550 million period of time, where's the erosion taking place in these layers?

Now, let me take one quick little step to back up. We're not talking about each of these necessarily being the surface of the earth for hundreds of millions of years at a time, what we're talking about is each of these layers being formed underwater. Now, this is very important. So geologists know that these are waterborne sediments. They had to have been formed underwater. So this layer here was formed under water, but how do you get a continent to be underwater, where you can create this layer? Well, plate tectonics, right? We're going to go a little bit more into plate tectonics next time.

But for now, just realize that plate tectonics can pull portions of a continent down, or an entire continent. Now, at today's rates, this would be incredibly slow, centimeters at a time, you would have a continent kind of sinking, maybe in the middle, maybe on the edges. And eventually the seawater would transgress, come upon the land, and then you'd have these shallow seas over an entire continent. So this is what the slow and gradual thinking is, right? Not taking into account any type of catastrophic event, such as a worldwide flood.

So if that's true, then the North American continent was underwater for hundreds of millions of years, produced this layer, then eventually tectonics would bring the continent back up. The water would drain off and this would dry, become hard, and then eventually plate tectonics would bring it down again, create another layer, bring it up, bring it down, create another, bring it up. You get the idea. And so, not just the North American continent, but all the continents that we have, supposedly this happened the same way: plate tectonics brought them down, raised them up after a flood, after these sediments were created.

So now we go back to our original question. Where is the expected erosion? Even underwater would have bioturbation. I would have living things that disturb these laminated layers. It's very, very hard to find these in the fossil record. It's very hard to find them. They're practically non-existent. Where's all this erosion that's supposed to have taken place at each of these increments. We clearly have it on top, why don't we have it underneath? Maybe, just one reason is because these didn't take hundreds of millions of years to lay down. They were laid down very rapidly. And in fact, so rapidly, if we look at it through the lens of the flood, that there wouldn't have been time for creatures to do any burrowing in, no bioturbation. There was very little time. In fact, that's what we see is very, very little of the sediments being disturbed in a turbidity type of a way.

Now, this is kind of interesting, right? Because people don't think about the entire continents being underwater at the same time, but being underwater at different times, but that's the kind of idea that we're being taught. I think it makes more sense to think this happened all at one time, these sediments were laid down very, very rapidly. We don't see the erosion, we don't see the bioturbation, we don't see any of the features that we'd expect to see down here, except trillions and trillions of dead things that are buried in these rocks.

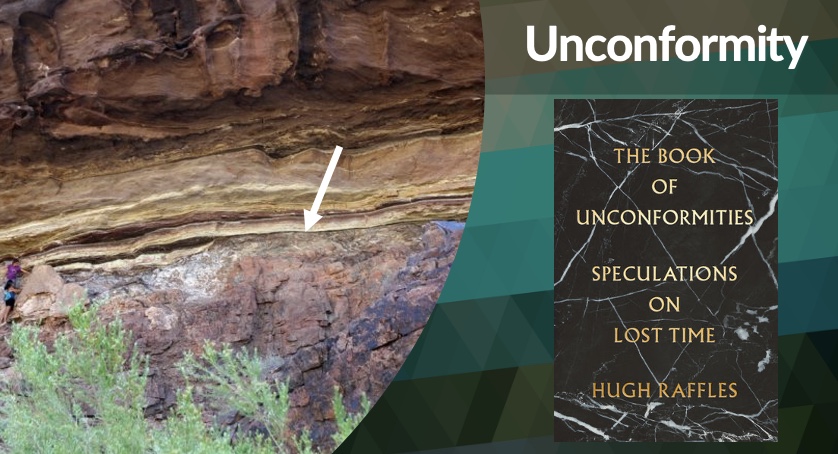

Now, the interesting thing about the Grand Canyon, specifically, is that we seem to be missing some layers. In other words, when scientists date these layers, we might date one as very, very old, and then one is going to be younger because it's on top. The law of super position, right? But sometimes the discrepancy between these layers and age-wise, with secular dating, is so large, they say, we're missing time here. There should be another layer here, but it's not. There's a term for that, they're called unconformities, meaning they don't conform. So we have a layer on top of a layer that appears to be missing one or more layers of time. Interesting, right? Missing time. Where are these layers at? We're going to come back to this idea of unconformities in just a moment. So let me finish out this slide and we'll talk more about this interesting phenomenon.

Now, scientists have done experiments using turbidity simulators or they've had sediments, they put them through rapid flow sediments of different kinds: sands, and grains, and rocks. They put them through these simulators, and what they see is when these layers are rapidly laid down, you've got a little bit of mixing, right? Because the water is rushing, you have these sea swirls. We would expect to find these in the Grand Canyon and really other rock layers, if they were laid down during this massive catastrophic event of the global flood. And in fact, we do see this mixing. I've seen some of this mixing myself in the Grand Canyon, where you have one layer, kind of, mixed into the next and one layer mixed into the next, and so forth and so on. That is not to be expected if they were laid down very slowly, centimeters at a time, inches at a time, over millions of years. But yet we see that. So again, another evidence of rapid deposition, or rapid depositing of these muddy sediments in a catastrophic event.

All right, let's go back to this idea of unconformities. This is one that I actually got to see and touch. It's kind of interesting. This is called the Great Unconformity. There are lot of unconformities, innumerable amounts of unconformities, missing time, but this one is the greatest. This is the biggest one. And I've drawn an arrow here, you can kind of see the people way over to the left for scale. So we have this clear line here, there's clear delineation between this rock and this rock. This is basement rock. This is, I believe this one's called the Vishnu Schist. It's an igneous rock. In fact, most of North America is resting upon this type of rock. You don't find fossils in igneous rock, no fossils. The process by which it's made would destroy any living thing, because of the heat.

And then right on top of it, you've got the Tapeats Sandstone. Now, when they date the igneous rock here, they date it- secular dating - 1.7 billion years old. When they date the sandstone, it's 525 million years old. You see the problem? 1.7, 525 million. There's a little over a billion years missing, of time. Now, what they say, there's two possibilities. One way of looking at it is that this layer between here was laid down, in fact did accumulate, but then something eroded it away, left no trace of it. And then this sandstone came on top of it; or that during this one billion year of history, which by the way, is a quarter of the Earth's entire history, if you're looking at it in terms of old age, or during this one billion year-long period, no sediments were laid down.

Either way you look at it, you've got a problem with both those ideas. What could have eroded that away and not left any trace of it, or why didn't the plate tectonics bring the continent down like it had been doing over and over and over again? In fact, I was just looking at a paper yesterday by Doctor Blakey, Emeritus Professor of Northern University of Arizona, I believe. And he had written a paper on the 38 different plate tectonic events, just on North America alone, all these 38 steps. Step-by-step, how it sunk, came back up. The Western and Eastern coast were sunk and then came back up, the middle sunk, and then came back up, 38 individual events, over this 500 million period. But yet, if one of those options is to believe that over a billion years, there was no plate tectonic activity that would pull the continents down and flood them, it's got problems.

Now, this isn't the only unconformity, like I said, this is the great one, it's sometimes referred to as Powell's Unconformity. In fact, there are 14 major unconformities in the Grand Canyon alone. Now, not all of them with this great amount of time, obviously not a billion years. Some of them are a hundred million years, some 160 million years, some are in the tens of millions of years. In fact, there is more time missing, there are more layers missing in the Grand Canyon, than what we have represented in the rocks, if you go by the conventional way of thinking about it. Interesting.

There are lots of layers in the Grand Canyon, but yet they only represent one-sixth of the total amount of time in Earth's history. Now this opens up a whole lot. If you're a critical thinker, you should be thinking about a lot of interesting questions right now. And maybe we'll cover those in the next session when we talk about plate tectonics, we don't have time today.

In fact, there's a book, The Book of Unconformities, and I love the subtitle here is, Speculations On Lost Time. Because that's really all it is, is speculation. Were those layers there? Were they not there?

Now, if we're thinking about this from a creation point of view, there is a way to look at this that would actually explain some of these unconformities. And we'll talk about it in a moment when we create our biblical flood model. Okay. And before we do that, we really need to go back to scripture, all right? So we need to look at a few scriptures, then we're going to create a model.

People always ask me, "What do you mean look at the world through the lens of scripture?" Well, if I'm a scientist, how do I build a model based on the Bible? The Bible is not a geological textbook, is it? No, of course not. However it touches on geology. When it talks about a global flood, when it talks about the fountains of the deep. Do you think this would have had an effect on the geological surface? Of course, right? It doesn't give us a lot of details, but it gives us a starting point.

And so we need to build our model based on scripture.

All flesh that moved on the earth perished, birds and cattle and beasts and every swarming thing that swarms upon the earth, and all mankind;

- Genesis 7:21

And then in 22 of chapter seven

of all that was on the dry land, all in whose nostrils was the breath of the spirit of life, died.

- Genesis 7:22

We're going to come back to that in a future session. And then in the latter part of 7:23,

Thus He blotted out every living thing that was upon the face of the land, from man to animals to creeping things and to birds of the sky, and they were blotted out from the earth; and only Noah was left, together with those that were with him in the ark.

- Genesis 7:23

And then 7:24

The water prevailed upon the earth one hundred and fifty days.

- Genesis 7:24

The Hebrew word here is like strong, the strong water.

There was some kind of strong currents going on for 150 days. And there's more scripture we could look at, but for time sake, you get the idea, we go to scripture and then we build this model that we can now take into the world when we're looking at these rocks, and then interpret them through the event of the worldwide flood.

Flood Model

All right. How do we do that? Well, we start with the 40 days of rain, Genesis 7:11-16. Now, this would have been probably, well, we weren't there and we don't have an eye witness observation into this, but again, looking at the rocks, this would have been the most devastating part of the flood. When the fountains of the great deep, the Bible talks about, opened up and we'd had massive volcanic activity, that this is what we think the fountains of the deep were. Again, we're going to do this in detail in the next session, but going back to that unconformity, this first part of the flood would have totally eroded whatever sediments were on the earth at the time, because I don't believe Adam and Eve were walking around on bedrock, on igneous rock, ouch. I don't think that's the case at all. There must have been sediments on top of that. This would have totally erased those. Talk about a great unconformity, here's what could have done it right here.

What do we have next? Now we have 150 days of strong water, Genesis 7:17 through 24. So the 40 days of rain was very catastrophic, and then we had 150 days where the water just kept rising and rising and rising. We'd have all these strong currents, we'd have underwater mudflows, lots of catastrophe going on.

And then the water subsides for 70 days, meaning that, after 70 days, the water's going to start draining off, and then you have 104 days of drying. Now, that water subsiding, think about that just for a minute. If everything is covered, all the high mountains everywhere, we've read before in one of our sessions, everything was covered. And so as the water would have started draining, you'd have had these massive sheets of water draining off the continents. And you know what water does. It may start off in sheets, but then it gets very channelized, doesn't it? You see this when it rains in your own backyard, you can see these little channels forming. At first, you may see running water, but then you very quickly see these deep channels, the scouring of the earth. That's going to leave a mark, as I always say, right? We should be able to look at a high level of scarring in the Western U.S., over into the Middle East, the UK, everywhere. We should be able to see this scarring effect, and we do. And then we want to frame all of this within the year timeframe of the flood, right?

And then we have this post-flood activity, the Bible doesn't talk about these post-flood activities. This is why I have observations written out to the right, because we see the layers that would have been laid down in the year-long flood, but then we see intrusions and we see evidences of earthquakes and massive volcanic eruptions. This must've been post-flood. So this is why I say these are observations. The earth would have been settling down for quite some time, according to geologists. And again, we'll look at this in a little bit more detail next session, but maybe up to 500 years, 200 years you'd have had the earth with just lots of activity still going on, volcanic activity and whatnot.

In fact, one of the creation scientists that I follow, says the ice age, the one and only ice age that would have happened, would have happened here, obviously, because this event, as we'll see through plate tectonics, would have warmed the oceans. You would have had massively warmer oceans, cooler continents. That would lead to an ice age, right? So lots of interesting things here that we can see through observations in the rocks. So this is our model.

We take this model, and then we go out to the rocks and we examine them. And then we can even try to figure out maybe which layer might've happened in what section. You know, think about those sea creatures. If the fountains of the deep started in the oceans, which there's evidence that they did, what would have been buried first? We've talked about this. Shallow marine creatures, where are they going to go? Where's that trilobite going to go? It's not going to go anywhere. So they would have been buried first on the very lowest layers. Fish would have been able to swim away for awhile, but where's the fish ultimately going to go? It can't get out of water. Then it's going to be buried later in a higher layer. You get the idea. Then reptiles. And so there is a general order we should expect if the flood is true and we do see that.

Not in order of evolution, the rocks do not show the progressive evolutionary steps, but it does show a progressive order of burial. So this is what we mean when we say, we interpret the world through the lens of scripture.

Now, if scripture had not talked about a flood at all, or anything that touched on geology, we couldn't build a model like this, could we? And then all we could do is just speculate. We can even add a lot of things to it. I've seen Christian scientists with very, very complicated flood models. Mine is very simple because I'm simple minded. We could even add a layer down here on the very, very bottom, of creation rocks. If you think about it, when God said, "Let the dry ground appear," that was some sort of tectonic activity. I mean, it must have left some kind of evidence, right? And we do see that. So you can make this as complicated as you want, mine's pretty simple.

So based on this model, I think we can conclude when we look at the real world that the trillions of fossils around the globe are mostly from this catastrophic event of the Genesis flood. Why do I say mostly? Well, not everything would have become a fossil, even though we've got so many fossils, if we think about it, some of the things like mammals, they don't necessarily, when they're drowned, they don't necessarily sink right away, they kind of float in the water. The animals that were on the ark wouldn't have became fossils, right? Not right away, because they were on the ark. Now the majority of everything alive would have probably become fossils, but not everything.

Rapid Deposition

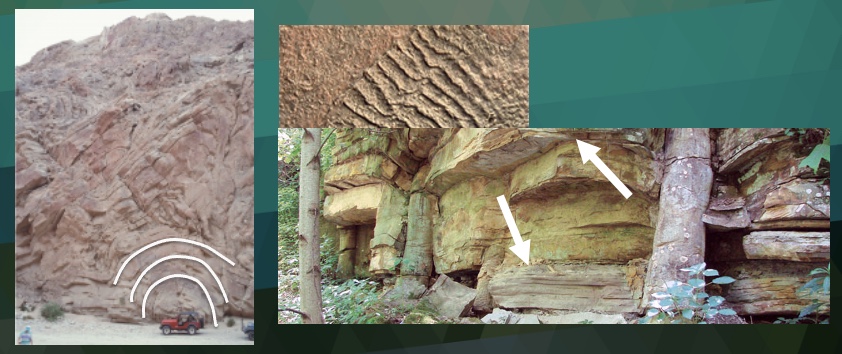

All right. So should we expect to find evidence that these rock layers were laid down quickly? We're looking at our model. Our model says this all had to happen in less than a year's timeframe. That's a very rapid geological timeframe. So what evidences do we have? I'm not sure if you can see this, but down where this Jeep is, you can see the strata, this rock, you can see it's arched. Now, how do you bend a rock? We bend wood and we can bend trees and that sort of thing, but how do you bend solid rock? Well, there are lots of complicated theories as to how this solid rock got bent and it has to do with thrusting it down to the mantle, bringing it back up, thrusting it down, bringing it back up. That doesn't make sense to me because this rock is fossil bearing.

Anytime you superheat a rock, you know, melt it, you're going to destroy the fossils that are in it, but that's not the case. I think it makes more sense to look at this as when this mud was still drying, right, that there was a tectonic event that had bent it while it was still very pliable, and afterwards, it just dried in place. I've kind of outlined it here. You can maybe see a little better, but it is bent. And the way it's bent is pretty incredible. It's 180 degrees down here at the bottom. So it's going up this way, and then it's going down on the other side, that's 180 degree bend in about what would you say? A 15-foot area. Pretty impressive. Rapid deposition, no other better explanation in my mind.

In the next image we are looking at a fossil ripple mark. Now, I love going to the ocean, love going to the beach. If you have ever been snorkeling around a beach area and just look at the sandy bottom, these ripples are quite beautiful. What happens to these ripples? A wave comes in, creates the ripples. How long do those ripples last? Only until the next wave comes in, erases the ripples that are there and creates another set of ripples, maybe in a different design pattern. So these are very, very short-lived. How do you fossilize ripple marks? Well, there's only one possible way. You have to bury them very quickly before any other wave could come in and rework that ripple, it's the only explanation.

Onto the next image. You've probably heard of these before, of trees found in sedimentary layers that actually cross through multiple strata or multiple layers of rock. Now, I've kind of pointed them out here with the arrows. You can tell that this bottom rock is a different type of rock than this middle rock, and then there's another one up here on top. And you can kind of see the lines in this fossilized tree on the far right. There's another fossilized tree there, there's another one there. But again, going back to the idea of slow and gradual. What tree in its right mind would wait patiently for a million years for mud to accumulate and harden around it and to become a fossil before it rotted and fell over? No tree. Not in its right mind anyway. You know, what makes better sense, is that these layers were laid down very rapidly, buried this tree rapidly, where it was. And we've learned that this kind of thing can happen through recent events in history, geologic history, like Mount St. Helens, for example. We'll talk more about that in a moment. So this idea of slow and gradual around the whole surface of the earth, doesn't make sense.

Now, I will say this, that in recent papers, maybe the last five, 10 years of geological papers, they do talk about localized floods. They're getting more and more used to this idea of localized catastrophes. Now, never will they abandon the overall slow and gradual, because evolution demands that deep time. You have to have that deep time. However, they are admitting when they find, for example, whales and birds fossilized together, mmh. Something catastrophic had to happen there, right? So they're coming around to this idea. Maybe in another 100 years they will budge off of this slow and gradual. Who knows? But for now, I think the evidence kind of speaks for itself.

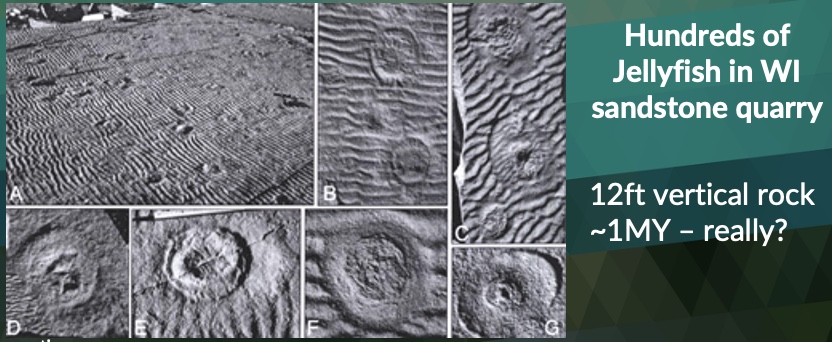

What about jellyfish? If you've been to some of the beaches here in the U.S. you've probably seen jellyfish. I've seen my share of them in and out of the water, but what happens when a jellyfish becomes stranded on the beach? Does it become a fossil? Nah. It's scavenged usually, right? There are critters on the beach that will start attacking it, the birds. They don't last very long. But here we've got hundreds of jellyfish found in the Sandstone Quarry in Wisconsin, and the amazing thing is that they were fossilized in sand.

Now, what's so amazing about that? They're jellyfish. Of course, there would have probably been sand around. Well, sand is a large grain type of sediment. Where if you think about like, just dirt, you know, outside your home, it's a fine grain.

Now, why is that significant? Because sand, when it buries something, there's so much room, there's lots of room between those sand grains. Oxygen still gets in and starts decaying living things. It's really hard for something to fossilize in sand, when you've got all this oxygen coming in and decaying it right away, especially jellyfish. There's no hard parts on the jellyfish. It's 100% soft parts. In fact, it's mostly made of water. So it's absolutely incredible that we could even get this in the first place.

Now, what they say is that these jellyfish got stranded on the beach, some kind of freakish tidal wave or something like that, and then sand washed over them and they eventually became fossilized in this rock that was 12-feet tall vertically, that took 1 million years to accumulate. How does a jellyfish become a fossil over a long- even a 1,000 years, even a 100 years, even a year, let's just be realistic. There's no way. This thing would have decayed and rotted. So not only is it insane, but you would have had to have a massive amount of sand, lots of heavy sediments, right, mineral borne sediments, getting it out of the environment, out of the oxygen, then you're going to get a fossil.

Okay. Now, look to a little bit more of a modern look at how quickly some of these things could happen, because we're talking about rapid burial. What's this idea that something can become a fossil very quickly? Can rocks form very quickly? Well, there was a paper done by a Professor Max Coleman, emeritus professor, geology of environmental sciences at Redding University. And he studied these marshes over in the UK. And I've got a quote, I've got a couple of quotes here, we'll kind of go through them, it says

Without regard to the laws of geology, mud on the marsh is hardening into stone in a few years rather than the thousands it usually takes.

- Max Coleman

Emeritus Professor, Geology and Environment Science

University of Redding

Now, let's talk about this statement for a moment. What are the assumptions in this statement? Well, one is that it takes a thousand years for mud to turn into stone. Is that true? Well, obviously not. Here, it's happening in a few years. In fact, we'll find out in the next quote it's happening in even less than a few years. So there's an assumption that it takes a long time for rock, for mud to turn into stone. But observation says that that's not necessarily the case.

The other thing I want to point out here is this idea of laws of geology, right? Like somehow there's a law in geology that says it must take thousands of years for mud to become stone. Well, somebody had never told the mud about this particular law because it's violating that law. And we go on,

Fresh from spending a week up to his neck in a muddy ditch in the marsh, Professor Coleman said the rock was forming faster than anybody had ever believed possible, with one stone creating itself in just six months.

- Max Coleman

Emeritus Professor, Geology and Environment Science

University of Redding

This is observation, right? Here's a marsh. We have muddy sediments being washed up on the bank and solid rock forming in less than six months. It gets even better than this,

They often contain beautifully-preserved fossils, where the detail of the soft flesh of the creature is caught as well as the bone, as it had no time to rot before the rock formed around it.

- Max Coleman

Emeritus Professor, Geology and Environment Science

University of Redding

Wow. Incredible. Think about amber or sap on a tree that drips down and maybe there's an insect that's eating on the bark, not paying attention, and just gets overcome by the sap. Where's it going to go? It can't go anywhere, right? Kind of similar idea here.

There's creatures in the mud, as this mud is washing in and they get washed over in the mud. They're becoming fossils in a very, very quick amount of time. Now, in this lesson, this year timeframe that we've been talking about here, there's no time for it to rot. He talks about even some of the soft tissues, right, beautifully preserved, like the jellyfish. And jellyfish isn't the only example we have. We find fossilized lobster with the antenna, very soft parts that would normally break or decay away very rapidly, are preserved in the fossil record.

Now, we don't see that everywhere. I want to make this very, very clear. Everywhere we look into rocks, you don't see these fully formed, beautifully-preserved fossils. No. We see a lot of damage to these animals. We see broken bones, mostly broken bones everywhere, when we're talking more about animals, sea creatures is a little bit of a different story.

So if we want to think critically about this, how does Professor Coleman's observation in the marsh relate to our flood model that we just created, that points to rapid burial? Well, I think it points very nicely to the fact that you can have rocks forming over a very short amount of time. You can have fossils forming over a very short amount of time, and this is with human observation. This is what the scientist is doing, going back to the same spot over and over again, and writing these things down. Observational science, which is what I wish we could do more of in some of these historical-type of sciences.

So let's go back to our scripture as we close out. Genesis 7:21,

All flesh that moved on the earth perished, birds and cattle and beasts and every swarming thing that swarms upon the earth, and all mankind;

- Genesis 7:21

I don't want us to lose sight of the fact of why we had the flood in the first place. You know, in geology, there's a term that I find very interesting. They use the word transgression. Transgression, meaning the shoreline transgresses upon the land.

So in our case earlier where the continents were sinking, that shoreline gets further and further inland, until you have an inland sea. They call that a transgression. The Bible also talks about a transgression, it has nothing to do with geology, but the transgression in the Bible is when humans violate God's will, when they choose their own will over what God's will is and what He's told us that He wants to see from us.

And when we go back to this Genesis account, transgression comes to mind. This is the reason that the whole earth was flooded to begin with, is the transgressions of the humans that He had made, who had gone their own way.

In fact, the verbiage in Genesis six says that, man's intentions of their thoughts were only evil all the time. Now, you look in today's society you may think, "Man, there's a lot of bad going on, a lot of shady characters, whatnot," but I don't know if it compares to the condition of the human race at this time. So we don't want to lose the fact, in looking at the science and looking at kind of the fun aspects of this, that this is a very serious catastrophic event. It was a judgment, it was God's judgment on sin, which He takes very, very seriously and so should we.

Thank you all so much for your attention on this session. Next session, we will try to answer the question, "where did all the water come from that could have buried everything, covered the whole earth," and equally interesting is, "where did it go after the flood?" So stay tuned for that.

Thank you for your attention.