Extreme Extinction Event!

Part 3 – Water Everywhere

Welcome to our next session of Literal Genesis. We're here, you probably know this by now, where our goal is to hold firmly to Scripture and hold loosely to the theories of us flawed human beings. Why do we hold firmly to Scripture? Because it never changes. In fact, when we read of the Genesis account of the global flood in Genesis 6, 7, and 8, it's read the same way it has for thousands of years. It hasn't changed. However, theories by men change all the time.

Take, for example, the tree of life that Darwin first came up with, where you had one single ancestor that gave birth, rise, to all the other living organisms on the planet. How many times has that changed? It changes all the time. In fact, since we've been comparing DNA between different species of animals, those lines have been redrawn, erased, drawn vertically, drawn horizontally. We've got dotted lines everywhere. It's a mess, right? Constantly interchanged.

So, we hold loosely to theories. And the reason I kind of emphasize that on this session is because I'm going to be talking about a theory that happens to support a global flood, evidence of a global flood. But again, it's a theory. So even when I'm talking about a theory, do the same thing. We hold loosely to those theories.

Now, last session we talked about evidence of rapid burial. We have all these trillions of organisms all over the earth, and we looked at one specific kind of animal that was buried in the Grand Canyon, in the Redwall Limestone.

Today, we're going to ask the question, "Well, okay, if we had a global flood, where might the water have come from? And where did it go at the end of the flood?" And so that's the part where we're going to kind of get theoretical, but it's based on actual observational evidence. So, again we should hold loosely to theories. We hold tightly to Scripture.

Before we get too far into it, I want to ask the question, well, why does it matter? Well, if Genesis is a historical narrative and is to be read as history, then that means something for Christians. We can't take the ideas of things that are contradictive and try to make them somehow match the history in Genesis. We have to read it as a historical narrative. In fact, there really was a worldwide flood if Genesis is history, which I believe it is. I don't believe it can be taken any other way. Which means the entire universe and everything in it is approximately 6,000 years old. Now, that's going to sound very strange to some of you because we've been indoctrinated with this idea that things are really, really old- billions of years old. But, in fact, if we look at Scripture, we can break it down roughly into three parts: about 2,000 years between Adam and Abraham. And remember, we know when Adam had Seth, we have a bookmark of all these genealogies, we can kind of add them up. It's about 2,000 years from Abraham to Jesus and about 2,000 years since the time of Jesus to the present. Now, this is going to be give or take 200 or 300 years, right? Not millions. Just a few hundred years, that it might be off from the 6,000. But it's really, really close.

This means that when we look at the rock layers, they can't be millions of years old. They have to be more recent than that, since the flood happened roughly 4,500 years ago, definitely less than 5,000 years ago. And also when we see the fossils in the fossil record, that can't be a record of slow and gradual evolution, as some say it is. We've got 6,000 years to work with. And we have a better explanation for it anyway. The global flood has amazing explanatory power when it comes to the sedimentary layers, when it comes to the fossil record. Now, we're going to deal with age in a future session. So right now don't worry about the age too much, but just know we have about 6,000 years to work with, if we added up the genealogies in the Bible.

Sedimentary Rock Layers

Okay, so we're going to take a look at the sedimentary rock layers. And this is a beautiful representation of what I'm talking about. So sedimentary rock is where we're going to find the fossils. We don't find fossils in igneous rock, like volcanic rock. The processes that make those rocks would destroy any living thing or dead thing that it buried. The sedimentary rock are going to be things like sandstone, limestone, shale, carbonates, silt, mud, clay, things like that. The sedimentary layers are going to be where we find the fossils. And one of the things you may notice when you look at a picture of sedimentary layers like this is these nice stratified layers. You've got straight, straight, straight. You can see the different colors of the sediments. And then at the top, it's eroded, it's bumpy, right? Like we would expect a surface to be. It has erosional features.

So, the question we're going to ask today is, where do we get these sediments? Because these are waterborne sediments. They all just agree that these were laid down by water. Now, what they don't agree on is that some say, "Well, these layers were laid down during the flood." Others may say, "Nah, each layer took millions to hundreds of millions of years to lay down very, very slowly and it slowly buried things."

We've talked about this in previous sessions. That idea doesn't make sense, does it, that you can slowly bury a creature for thousands of years while it fossilizes without it completely decaying away, without scavengers taking it and eating it. So those ideas, the slow and gradual, doesn't really make a lot of sense. It never has. Quick burial, that's what you've got to have to bury and create fossils. So we start with Scripture, and I picked the second half of Genesis 7:11 to start with. And it reads,

"On that day," this is the day that the flood began, "all the fountains of the great deep burst open, and the floodgates of the sky were opened."

- Genesis 7:11b

So this is our clue, right? The flood started somehow with "the fountains of the great deep." We're going to look at maybe what that was. And "the floodgates of the sky were opened." So this doesn't sound like a tropical rain, does it? I've had the pleasure of going on vacations to many tropical places, and nearly every tropical place I've been, you get this nice little rain that comes in in the afternoon. It's not enough to damper your activities. You're going to stay outside. You're going to be in this light shower. And it's kind of refreshing, right, when you're in the tropics. I don't get the feeling this was that kind of a rain. We're talking about the "fountains of the great deep" and "the floodgates of the sky," so I think this sounds like a very catastrophic event. Let's see if we can get some other clues here.

Where Did the Water Come From?

Okay, so we've got a lot of water on the earth already. So when we're asking the question, "Where did the water come from?" I think an obvious source to look at would be the water we already have, because we know that the atmosphere can't hold enough water to flood the earth and cover all the continents. In fact, the atmosphere can hold about enough to cover the entire globe in one inch of water. So the water probably didn't come from the atmosphere. Now, having said that, do we really need a scientific theory on where the water came from? I mean, wasn't that verse enough, Genesis 7:11? That's enough for us, right? If we're Christians. However, it's interesting to be able to research this and see that there is a scientific explanation that actually works.

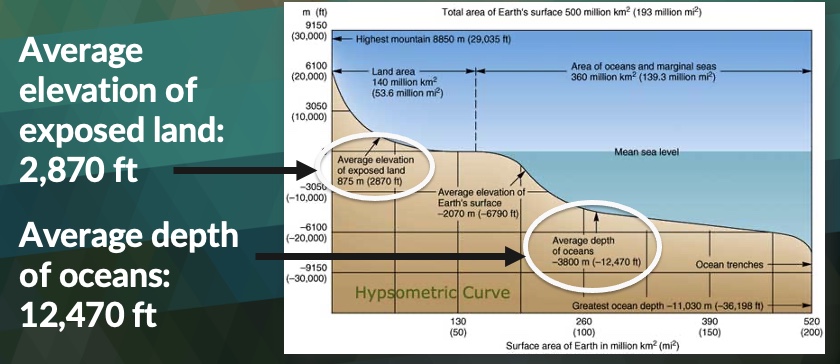

Now, this is a theory. I want to make that very clear. What I'm about to tell you is a theory as to how this water may have gotten on the continents. But first let's ask the question, "Is there enough water to even do that?" We know we have mountains as high as Mount Everest, about 30,000 feet. We've got ocean depths as deep as around 36,000 feet. So right off the bat, it looks like maybe there is enough water.

The average elevation of exposed land is right around 2,870 feet. And the average sea depth is around 12,470 feet. So it looks like we have enough water. But if you look at this, you may be thinking, this is not three-dimensional, is it? We're only looking at height. We're only looking at one axis, height, all across the scale. So we need to ask the question, "What about three-dimensionally? What about the volume? Do we have enough ocean volume to cover the continents?"

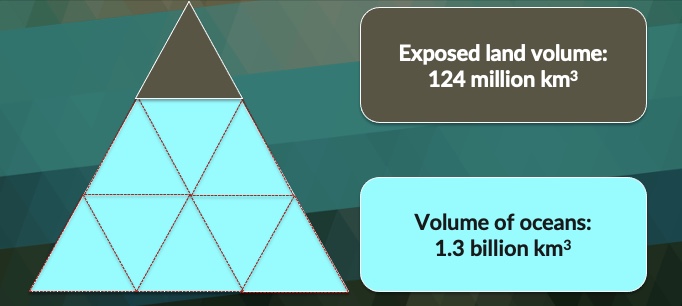

Well, if we look at the amount of exposed land, the land that sits above sea level, it's about 124 million cubic kilometers. Now, don't worry about the cubic kilometers part of it, if you're not really familiar with math or the metric system. Don't worry about that. You don't have to translate that. We're really going to focus on this 124 million. And if we look at the volume of the ocean, again, three-dimensionally, it's 1.3 billion cubic kilometers. So which is the bigger number, 124 million or 1.3 billion? Well, that's a no-brainer, right? In fact, it looks like there's enough volume in the oceans that we could bury the earth 10 times over, 9 or 10 times. We have plenty of water in 3D space to cover the entire continents. And that's looking at today's continents with the big mountains. I don't believe that Mount Everest was around before the flood. In fact, many of our mountains we have today came after the flood. Why do I say that? Because those sedimentary layers that were laid down by the flood, and then the mountain building that would have happened after the flood. We'll look at that more later. So Mount Everest wouldn't have been around, that's a post-flood mountain event. But regardless, even if it was here, we've got the volume. We've got plenty of water to cover the earth.

All right, so let's go back to Scripture, and I'll see if we can get a little more of an idea before we run into our theory.

"Now it came about after the seven days, the waters of the flood came upon the earth."

- Genesis 7:10

Now, you think this would be enough, right? There's a lot of times in Scripture where we read and we think, "Oh, we'd just love a little bit more detail. Can we get a little bit more detail there?" Well, here God could have just stopped there. "Hey, the flood came. I told you it was going to come. Noah built the Ark, the flood came." But He gives us a little bit more info, which I find interesting. Look at the wording here in 7:11, the first part.

"In the 600th year of Noah's life, in the second month, on the 17th day of the month."

- Genesis 7:11

Now, why did I stop here? This sounds a little bit formal, doesn't it? Growing up, were you ever called by your first, middle, and last name by one of your parents? My mom did that to me on occasion. She didn't do it all the time, but when she did, I knew to stop whatever I was doing. Something momentous was about to happen. Usually I was about to get in trouble or I was about to do something really stupid and hurt myself. But this has kind of a formality about it, doesn't it? And we do the same thing today. Whenever we want to mark a momentous occasion, we record the day and the month and year. We do this, right? So I find this interesting that God could have stopped in the previous verse, but now we're entering this, it sounds like it's very formal. Something momentous is about to happen.

And then the verse we already read, "On that day all the fountains," How many of the fountains? "All the fountains of the great deep." What are those? I don't know. We're about to maybe have an idea. "They burst open and the floodgates of the sky were opened." This does not sound like a children's bedtime story about the flood, does it? This sounds like something very catastrophic.

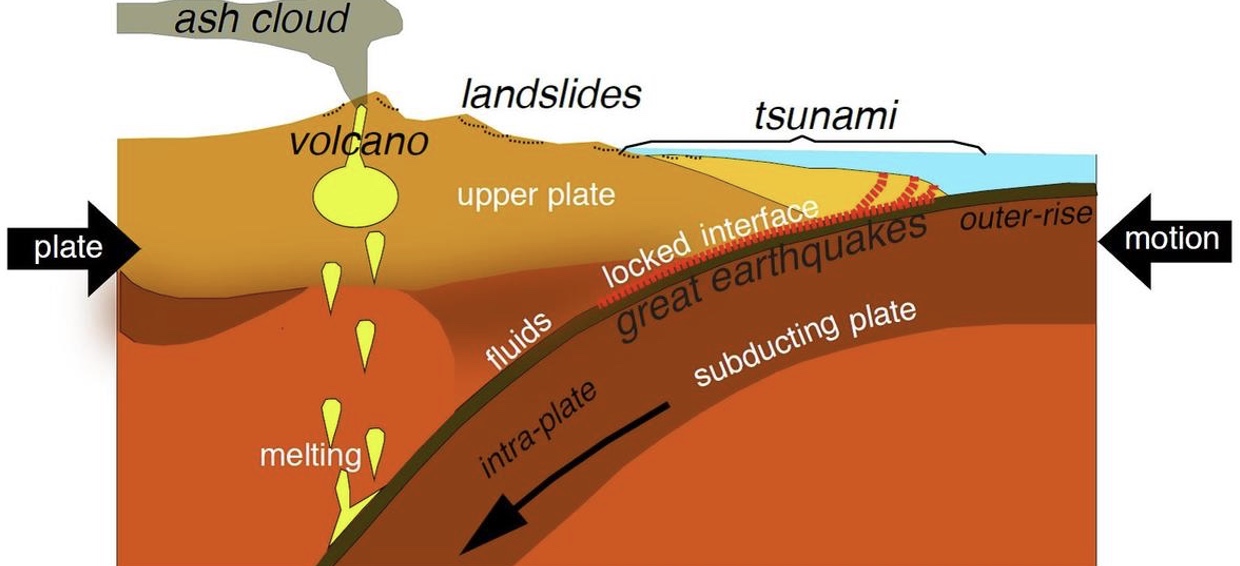

Okay, so where did the water come from? Before we look at that, let's look at an idea that you probably learned in middle school or high school in one of your science classes. And that's the idea that we have these plates around the earth. Whether or not those plates have always existed, that's perhaps another session, another time, but we have these plates today. And what happens is these plates are moving, right? They bump into each other. These are massive plates, right? Thousands of miles long, four miles to 25 miles thick. Big, big slabs of rock. And whenever these plates move, they can do several things. When they come together, they could slide, right, because of the tension. And that creates tidal waves and tsunamis and that sort of thing. Or they could buckle, when they hit, and they could create mountain ranges. Or one plate could slide under the other, and this is called subduction, when the plates meet and one slides under the other.

And this is what we want to talk about here today, these big plates under the oceans. Now, they're big, but they're smaller than the continental plates. These average about four miles thick. So you can imagine walking out your front door and climbing four miles up on top of this big rock. And when you get on top of this rock, it goes for 1,000 miles. That's a big piece of rock, isn't it? But it's not as big as the continental rocks, which could be about 25 miles thick.

So when these two rocks meet, the ocean plates sometimes want to subduct. They want to go under the continents. And they're going to carry a lot of sediment from the ocean floor with them. Now, this sediment is not very dense, it's a lot lighter, and it doesn't want to go down, it doesn't want to subduct. Like a beach ball doesn't want to go under water, these lighter particles do not want to subduct. So they kind of gather here and make the continental shelf. Some of it, very little, may be dragged down and superheated and come up through volcanic activity. This part is questionable even among geologists. We can't exactly see, this in the mantle, but this is what we think happens. But we know this subduction happens. However, this process is really, really slow, on the order of about three inches per year. So, you can imagine this plate slowly going under the continent at a rate of about three inches per year. This is what we observe today. So that's kind of the idea of plate tectonics.

Now, let's explore this in relation to what we just read in Scripture and see if we can get an idea. So we know we have enough water to cover the continent. The question is, how do you get the water on top of the continents and still have water in the oceans? Because Scripture is very clear that all the high mountains everywhere were covered, and we read that in the last session, there was water all over the earth. So you can't just drain the oceans and not have anything in the oceans. You have to get the water on top of the continents and still have oceans everywhere.

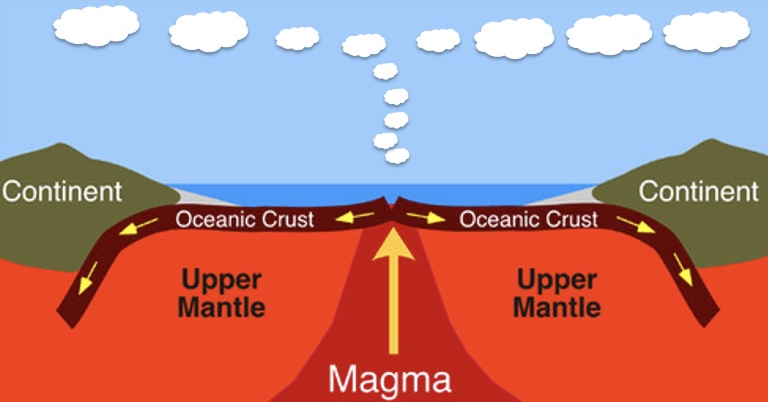

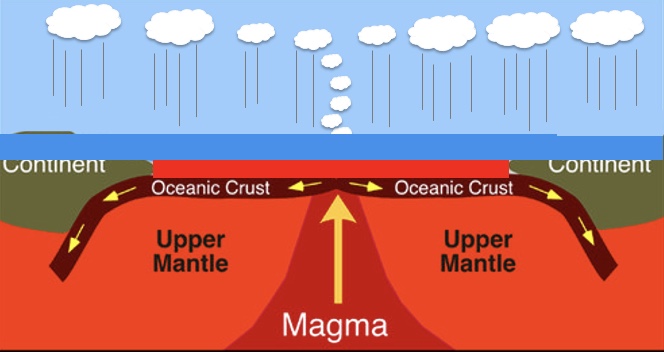

So this process of these plates subducting under the continents starts in the ocean where the sea floor actually spreads apart. This is observational. We see this today. And it forms this little ridge. In fact, it forms these underwater mountains. These mountains can be as high as 6,600 feet. So almost 7,000 feet. These are big underwater hills. When the sea floor spreads, this hot magma now is exposed to that cold bottom ocean water. Now, this happens at a very, very slow rate today, again, about one to three inches per year, that these plates are moving.

What if this process was sped up? This was the subject of some research done by a fellow by the name of Dr. John Baumgardner. He was formerly at Los Alamos Laboratories. He's a world renowned expert on plate tectonics. And he's modeled this on a computer. Now, just because you model something on a computer doesn't make it true, right? But he's plugged in all the data of the plates around the earth and had this idea of, well, what if this process was sped up? What if these plates moved quickly on each side, the sea floor spreading was massive, and we exposed more of this hot magma to the bottom of that cold ocean floor? Well, what happens is that hot and cold coming together would vaporize that colder water on the bottom of the ocean and send it up as giant plumes of steam.

Now, how big is this process on the ocean floors today? Well, imagine this rift being 40,000 miles long, going all across the earth. In fact, if you look at the plates, it kind of looks like a baseball with the stitching going everywhere. That's what these plates are. They're running all over the earth. They kind of come in contact with each other. And it's 40,000 miles long. So the steam would go up into the atmosphere, condense and fall as global rain.

This may answer one of the questions we have. How did it rain for 40 days and 40 nights all over the earth? Well, 40,000 miles of this hot, steamy vaporizing process, that would do it, that would explain it. That's one possible answer. Okay, well, 40 days of rain isn't going to cover the entire continents. It would cause some pretty massive erosional features, right? With all that rain for 40 days. This is a hard rain. This isn't the tropical rain we're talking about. This, we think, could be the fountains of the deep, and then this is the floodgates of heaven. So think of it that way.

Is this the way it happened? I don't know. This is just a theory, right? We're looking at processes that happen today and we're asking the question, "What if they were sped up?" And we can address how they might've been sped up a little later on. But there's evidence that they were sped up. We'll look at that.

Okay, so what else happened? When you have this hot magma coming up on the ocean floor and being spread across the entire ocean basin, what happens is- this is less dense material, so it's going to do what with the water? As it raises on the bottom of the ocean floor, what happens to the water? If you raise the bottom of a bathtub when it's full, where does the water go? Well, the water goes up; it has to be raised up. So you have this entire new ocean floor, which there is evidence of, a relatively young ocean floor, would have pushed up on the oceans, pushing them up over the continents. That's a lot of water. Imagine, 10,000 miles of oceanic basin just being raised up.

The other part of this is these plates are rapidly subducting under the continents. And when that happens, the model shows that they tug on the continents and they actually pull them down. And what would happen is you've got the water rising, flooding the continents, and you've got the subduction tugging down on the continents.

All right, this is what we think happened. Is there evidence of this? The evidence is when we look at today's process of these plates going under the continents when they subduct, this is so slow that these colder ocean plates are being heated up as they subduct at one to three inches per year. However, since the sixties, when we've been mapping out the entire ocean basin, what we see are these colder slabs of rock of previous ocean floor, giant slabs of rock that haven't had a chance to heat up yet, they're still cool. This process today, the rock is heated up as it enters the mantle.

Why do we have former ocean floor that's still cool and hasn't had time to heat up? Well, one possibility is that these plates were put down there very quickly. This rapid or catastrophic plate tectonics is another way to look at this. So that's one of the evidences. The other is that the entire ocean floor we see today is relatively young compared to the age of the continents. Now again, we'll look at some age issues in a later session, but even geologists will say, "No, the ocean floors are relatively young." And we've got this previous ocean floor that's been crammed down into the mantle, almost all the way to the core, that's still cold, cold ocean slab. Well, that doesn't make sense if it was subducting at a rate of three inches per year. However, if this was subducting at a rate of six or seven miles per hour, being drug down under the continents, that makes sense. Then you can have the colder ocean rock being thrust down and it just hasn't had time to heat up. Even in a couple of thousand years, it hasn't had time to heat up. Okay, so that's the evidence of the rapid subduction.

And it answers the question, where did the water come from? How did we get the water on the continents? And this tugging motion here, we're going to look at in the next couple of slides, that we think this happened in surges. A tug on the continents and then it would float back up, a tug on the continents, then it would float back up. And we have evidence of that as well.

So before we look at that, we're going to go to another part of Scripture. This is Psalms 104:6-8. Now, you may be thinking, "Why are we going to a poetic book? It's just poetry, right? We're not to take poetry literally, like we're to take the Genesis account literally, correct?" Well, yes and no. So just because it's poetry, does that mean it's not true? We read the 23rd Psalm,

"The Lord is my shepherd. I shall not want."

- Psalms 23:1

Well, is the Lord really my shepherd? Am I a sheep? Well, no, but we get the idea of this relationship, right? There's still truth in poetry.

And I think we have another clue that we have here about the water. And David writes,

"You covered it with the deep," he's talking about the earth. "You covered it with the deep sea as with a garment."

- Psalms 104:6

What does that sound like?

"The waters were standing above the mountains."

- Psalms 104:6

That sounds like the language we read in Genesis 7, when all the high mountains everywhere were covered with water. And he says,

"They fled from Your rebuke," talking about the waters, "At the sound of Your thunder they hurried away."

- Psalms 104:7

So waters were covering the continents and now they hurried away. Well, how did that happen? He writes,

"The mountains rose and the valleys sank down to the place You established for them."

- Psalms 104:8

Okay, this may be a clue that after everything was flooded, that the land was raised and the valleys were lowered. So that's the clue we're going off of.

Now, let's take this back to our model. So we have all the water covering the continents. We have this hot brand new ocean floor pushing the water up. What happens when this cools, this brand new ocean floor? It's not very dense when it comes out of the core from the mantle, right, this magma? But when it cools, it condenses. So what happens to that ocean floor? It's going to sink, isn't it? So when this rock cools, you see the animation (see video 23:10), it's going to lower the water. The other part of this is this rapid subduction is going to build these mountains. Here's where these post-flood mountains come into play.

So could this actually relate to the Psalms where it says He raised the mountains and He lowered the valleys? This seems to match, right? When the hot ocean floor cools, it's going to sink down. The water is going to go down. And this rapid subduction is going to build up the continents in many places, like the Himalayas, for example, where we get Mount Everest, 29,000 feet. So that's the evidence there.

Now, again, this is a theory. What do we do with theories? We hold loosely to theories, right? I'm not saying this is how it happened, but we have good evidence that this is how it might've happened. There are questions about what started this rapid subduction. And there's all kinds of theories on that. We can explore that maybe in another session as well, but there's evidence of rapid plate subduction under the continents.

Geologic Column

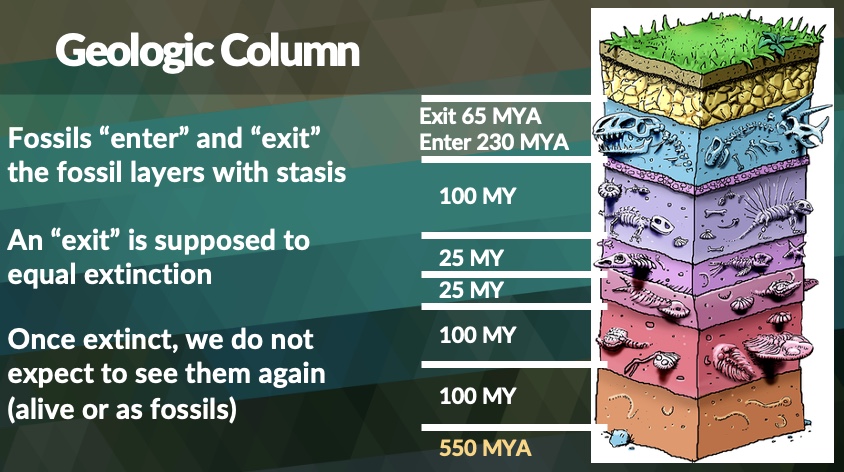

We're going to look at something called megasequences here in a moment, but there's a concept we really need to look at first, that I think needs looked at. There's a critical question we need to ask, and this has to do with the geologic column. So here's a simple representation of these layers. We looked at the picture at the beginning with all the different layers of that mountain. Well, if we're standing on top here on the green grass, literally underneath our feet is a graveyard of fossils, once-living things that were buried and became fossils. Now, according to traditional thinking about these long ages, each of these layers would have taken tens or hundreds of millions of years to accumulate.

We'll take the North American continent for example. Parts of it were underwater for millions of years. And then through tectonics, it raised up and dried. And then through millions of years, it subducted again, right? So geologists think the same way about the past, but they think it happened very slowly. Although today, we don't see subductions pulling continents down, allowing ocean waters to come on them. We don't see that. But that's supposed to be how it happened in the past- very, very slowly. And each of these fossils, we can see a progression, quote, unquote, from simple worms all the way up to dinosaurs and mammals, and then eventually us on top.

Now, these fossils, they enter and exit, this is kind of the wording that we needed to find, they enter the layers and they exit the layers. For example, dinosaurs were first seen, again, air quotes, 230 million years ago in the fossil layer. And the last time we see them, about 65 million years ago, there's still dinosaurs. So they enter the fossil record completely fully formed, and they exit the fossil record the same way, no change. And in fact, that's called stasis, this idea that things stay the same, if you want to think of it that way. That's a problem for evolution. If evolution is true, then these things were slowly changing into all these different life forms. We just don't see it in the fossil record. Darwin knew it during his day. 150 years later, we still have the same problem. No transitional species that I'm aware of.

The question I want to bring to the point here is, this represents 550 million years, supposedly, in earth's history. Now, again, if we look at the genealogies in Genesis and other places, the New Testament, we don't have 550 million years. We have about 6,000 years. But this is supposed to be 550 million years. However, the rate of erosion that takes place on the continents today would totally erase all of this in about 20 million years. Think about that. In 20 million years, this would be eroded down to base rock. Yet we're supposed to have 550 million years of history. How does that work? So does that makes sense? This is something that no one really addresses in any of the literature that I've read from any of the geologists.

At the current rate of erosion, now, geologists think that whatever's happening today is the same thing that's been happening for millions of years at the same rate. That's called uniformitarianism. Yeah, try saying that one five times. But if everything's happening today at the same rate, then all of those sedimentary layers that we have to see today would be totally wiped out in just 20 million years, but yet we're supposed to have 550 million years of history.

Fining Upward Sequences

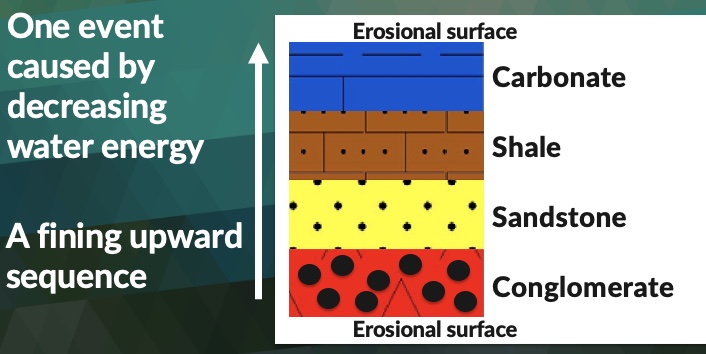

Is there a better explanation? Well, obviously I don't think the layers are that old. I think they were laid down rapidly very recently. In order to show that, we'll look at one more point here on these layers. And that is something called fining upward sequences. Now, what's a sequence? So in geology, a sequence is a set of layers like this that were laid down at the same time. So yes, geologists do believe that some layers were laid down at the same time.

And the reason that they think this is when we look at the order, it's always the same. At the bottom of these layers, we're going to have larger, heavier particles. So I want you to think about this in terms of the flood. As those continents are being drug down and as those ocean basins are being pushed up, we have all this sediment washing over the continents. And all the sediment's mixed together. We've got large particles, we've got small particles, it's all there, all tumbled together. And when we have these currents rushing over, eventually they're going to slow down.

What happens when rushing water slows down? Well, heavy things start to drop out of them, don't they? The first thing that's going to drop out is the heavier particles, could be boulders, could be gravel, cobblestones, something like that. And this is called conglomerate rock. The next thing that's going to drop out are the sandstones because they're the next heavy element, right? We've already dropped out the big boulders, so as this rushing water slows down even more, now you're going to drop down the next heavy element, which is sandstone. It's going to be coarse to fine sandstone. Then ultimately you're going to get to shale, which is the mud clay, which is finer particles. The water slows down even more, you're going to get the carbonates last that drop out. This is where we get our limestones.

So a sequence is going to be a set of layers that are laid down at the same time with moving water, with the current. To be a sequence, also, you have to have erosional surfaces at the top and at the bottom.

And you may remember the word we used in our last session, this unconformity, right? This missing time like we've seen in the Grand Canyon, for example. There are 14 major unconformities. Think about this again in terms of the flood, that first surge of ocean water that came over the continents, it's going to have these big rocks, these big boulders. It's going to scour the sediments that are already there. It'll erase them, is what will happen. And then as it settles down, the current stops, it's going to start dropping out these particles and creating these nice layers, just like the picture we've seen at the beginning of the session. So this is called a fining upward sequence, meaning we start with coarse material and it gets finer as we go up the stack. So it just make sense, right? This very, very light material, that's not going to settle down first. It'll be the last thing to settle. The heavy material, it's going to be the first to drop out when that water slows down. So this is one event caused by a decreasing energy of water. A flow that's moving can't move forever, right? It slows down. It's going to start dropping out these particles. So this is a fining upward sequence.

Megasequence

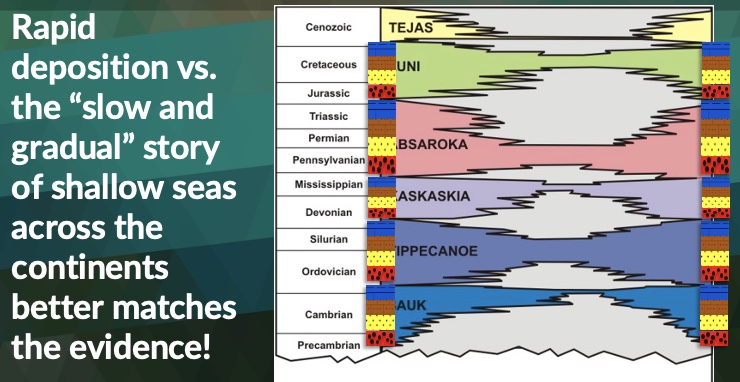

Now, to be a megasequence, we take those sequences and then think about it on a larger scale, like a continent-wide scale. This is called a megasequence. Now, this has been known for quite some time by Geologists, since the sixties. In fact, there's a fellow by the name of Sloss who worked for an oil and gas company, and he mapped out the North American sequences called the megasequences. In fact, they're called Sloss' Megasequences. That's another fun thing to say.

But the way to look at this chart here- well, first of all, on the right, these should be fairly familiar to some of us. You know, Cambrian. When we see these words, we automatically think of time, don't we? 550 million years ago. We think of Cretaceous or Jurassic being like 200 million years ago. Those timeframes are imposed upon the rocks. The layers don't have tags that say, "Hey, my name's Cambrian and I existed 550 million years ago for 100 million years." Those are imposed upon the rocks, as we'll see when we talk about some time issues later on.

We see this first megasequence down here, and these are named after North American Indian tribes. So we have the Sauk megasequence, and think of this width here as being the entire North American continent. We have western shore, we have eastern shore. And then this color here, it represents the mud or the sediments that we refine when we do the core samples. Like when geologists for oil and gas companies drill, they go down deep, they pull up the core samples. This is what they see. And they see on the eastern coast and the western coast of the North American continent, it starts out really thick, these sediments, and then it gets thin in the middle and thicker again on the side.

Now, this Sauk megasequence is supposedly laid down slowly over hundreds of millions of years, right? When the North American continent was subducted underwater. On top of that, we have what's called Tippecanoe. It looks like a similar pattern, doesn't it? Very thick sediments on the edge, very thin here, very thick here. And in fact, on and up to Kaskaskia, and on and up to Zuni, and then this top one here, the sixth one, is debatable whether it's a megasequence or not. It doesn't fully meet the definition of a megasequence, but it doesn't matter. We have at least five of these solid megasequences. So think about this as five surges during the flood. When the plates were subducting into the continent, pulling down like a cork in the water, allowing these sediments to rush over.

These sediments that came in are in a fining upward sequence in the Sauk megasequence. So they start with the coarse sediment and they go up to the very, very light sediments, like the sandstone. This is what we see.

In fact, when we look at the Grand Canyon, there's no better place in the world to see this than there, because it's all exposed. When the second bobbing down to the continent perhaps came, we had that second surge of rushing water, guess what? We have another fining upward sequence beginning with the coarse to the fine. And it's the same thing with the rest of these layers.

Now, some of these layers may not have all of the types of rock, but it's always in this order. It's always from coarse to fine. And we know that this happens with rushing water, with moving water. So this idea that this happened over millions of years in shallow, placid, calm seas, it doesn't make sense. You don't get these fining upward sequences in a calm sea. You have to have moving water for this to be deposited. Slow and gradual just doesn't make sense here.

So again, think about this in terms of the worldwide flood. Now, we're just looking at one continent here. You can do this for all the other continents on the planet, and they're going to have similar features. But again, this tells me this was a catastrophic event, these surges of ocean water coming in over the continents with massive amounts of sediment, scouring everything in their path. It's kind of a scary proposition, isn't it, when you think of it that way?

Now, let's look at a couple of quotes here from two evolutionary scientists who are studying these ideas of megasequences. And they say,

"The notion is still widely held that slow-moving currents or still water are a prerequisite for substantial mud deposition."

- John Southard, Juergen Schieber

Accretion of mudstone beds from migrating floccule ripples

Science 318(5857):1760; 2007

So they're saying the idea, even today, that's kind of predominant in geological science is that these shallow seas of the ancient past is enough to explain the rock layers.

He says,

"Our observations do not support the notion that muds can only be deposited in quiet environments with only intermittent, weak currents. Instead bedload transport of flocculated mud and deposition occurs at current velocities that would also transport and deposit sand."

- John Southard, Juergen Schieber

Accretion of mudstone beds from migrating floccule ripples

Science 318(5857):1760; 2007

These guys, they're evolutionists. They think in the evolutionary mindset that things are old and slow. But when they look at the layers with their eyes, with their brain, they're saying, "The velocities, we have to have rapid-moving water to make these sequences."

However, it's been my experience when I'm talking to a geologist or when I'm reading papers, is that their eyes tell them one thing: This must have been laid down very, very rapidly, with massive amounts of water and mud and that sort of thing. But when they go to write the paper, they go back to their training in college. Well, we know this took millions and hundreds of millions of years. So you see this dichotomy, right? You see this conflict in the papers. Their eyes and brain tell them one thing, but they know that can't be true. Interesting. We're going to come back to that concept.

To summarize what we've talked about today, there's more than enough water on the current earth. The surface is 70% water and we have the volume underneath to cover the continents and to still have oceans. The sedimentary layers must've been laid down very rapidly, right? Not over millions of years.

This idea of fining upward sequences, we know that happens only in fast-moving water. The entire ocean floor is relatively young, geologists will say, compared to the continental slabs. The previous ocean floor we've seen through a radio tomography. I don't think I mentioned how we do that. We fly a plane over it with tomography equipment and we see that there's massive amounts of previous ocean floor that is still cooler in the mantle. They haven't had time to reach equilibrium with heat with the rocks in the mantle. That can only happen if it got down there very rapidly. That's the only explanation. And again, this fining up sequence, this massive continent-wide episode, these surges of water coming over the continents, is the best explanation for how we have these rock layers in the order of coarse to fine.

So this fits the historical narrative of Genesis 6-8. Now, again, how this happened, I want to stress again, this is just a theory. This rapid idea, this idea of rapid plate tectonics, is just a theory. We want to hold on to that loosely. What we do want to hold onto firmly is the fact that there was a worldwide flood, and it happened very recently, and it destroyed living things. In fact, the land animals that weren't on the Ark, they were destroyed, they were buried, they became fossils.

Now, why do scientists look at this and make this disconnection here? They see with their eyes and they think with their brain that this must've been laid down rapidly, but they can't accept that. Well, I think Peter has an answer for us.

"Know this first of all, that in the last days mockers will come with their mocking, following after their own lust and saying, 'Where's the promise of His coming?' For ever since the fathers fell asleep, all things continue just as they were from the beginning of creation."

II Peter 3:3-4

Here, we have the idea of uniformitarianism, that things that are happening today, they've been happening the same way at the same rates for millions and hundreds of millions of years. Peter's saying, "People will mock us for saying, 'No, the past was different.'" And he goes on,

"For when they maintain this, it escapes their notice."

- II Peter 3:5

And some versions here of your Bible may say, "they are deliberately ignorant," or, "it escapes their notice."

"By the word of God the heavens existed long ago and the earth was formed out of water and by water."

- II Peter 3:5

Which, by the way, violates the Big Bang idea that the earth started out as a hot, molten blob, right? Here, Scripture says, no, it was cool. It was covered in water. He says,

"through which the world at that time was destroyed by being flooded with water."

- II Peter 3:6

What happened to the world, did Peter say? It was destroyed by water. A cataclysmic event, catastrophic event of water.

And again, this idea that, you know, the world mocks us for thinking this way, yet the evidence is on every single continent, everywhere we go, every core drill sample that we take, shows that something catastrophic happened in the past.

It's not exactly a children's bedtime story, is it? At least not the way presented here in Scripture. I don't want us to lose sight that the reason that God flooded the earth to begin with, if we go back to Genesis 6, it says, "the intentions of the thoughts of the humans that He created were evil all the time."

So His very good creation had become corrupt, and He punished the evil by flooding the earth. On the flip side of that, God saved a family, a family who found favor in His eyes, a family who was obedient to Him.

So it's a picture of not only judgment of how God feels about sin, but it's also a picture of salvation and that God knows how to rescue the godly people who do obey Him and worship Him.

Well, thank you for your attention today. I will give you a little sneak peek of the next session here. We're going to talk about the Ark. I think that's one of the questions that comes up a lot is, "Okay, Noah built this Ark. It really looks like there was a worldwide flood. We have plenty of evidence for that. But how do you save all these animals on a single boat?" We're going to take a look at that closely next time. Again, thanks for your attention.